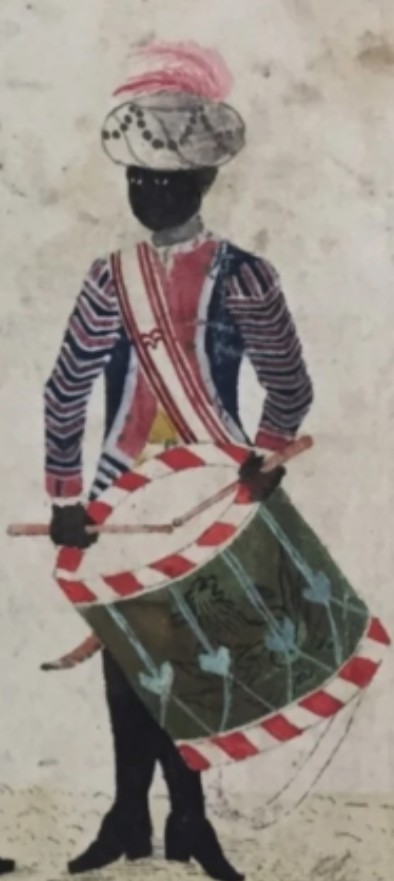

Several years ago while researching Count von Donop’s occupation of Burlington County, I came across an interesting note related to the von Minnigerode Grenadier Battalion, who for a brief time was quartered in Bordentown, NJ. It showed that a black man named Prince Lewis had enlisted as a drummer for the Hessian battalion on the 10th of December 1776, during the first day of von Donop’s occupation. Lewis’s background is murky, but it is clear that he was 26 years of age, a capable musician, and from Bordentown. If the Minnigerode records are to be believed at face value, then it’s perhaps beneficial to point out that they listed him as “recruited”, meaning the decision to do so would have been Prince’s alone. If this notion is true, then it offers a very striking example of ironic contrast in Bordentown. How can it be that Thomas Paine, the writer of one the most influential works on American liberty and endurance of the cause exists in the same small town as a willing Hessian recruit? On the surface this shows us the true dynamic of how different individuals felt about the war, however, on a much deeper level it presents the idea that liberty and perhaps even independence could carry a different vision and personal meaning.

Whatever his reasons, Prince Lewis was now part of a military organization in an active campaign. Depending on whether Lewis was issued his necessary equipment in time, it is possible that he partook in von Donop’s advance on Burlington the next morning after his enlistment. One hopes that Prince Lewis hoped for adventure, as the Hessian command he joined would see its lion’s share. Only a week and a half later, fighting would again erupt in Burlington County, this time at Petticoat Bridge and Iron Works Hill in Mount Holly. Here, Prince’s regiment played a pivotal role in driving back Colonel Samuel Griffin’s New Jersey militia. The shocking defeat at Trenton caused von Donop’s command to scramble up towards Allentown rapidly to avoid being cut off from the rest of their army. Only a few days later the Minnigerode Battalion took part in the battle of Assunpink on January 2, 1777, remembered as the bloodiest of the “Ten Crucial Days.” That remaining winter into the spring, Lewis quartered in northern New Jersey and found himself as part of a growing guerilla conflict remembered as the “Forage Wars,” which ravaged the regions between Morristown and New York. Donop’s command spent their time in Brunswick undertaking expeditions and engaging in irregular warfare through that area.

In just a few short months, Prince and his comrades were on Royal Navy ships heading towards the Head of Elk in Maryland, beginning the largest campaign the war would see. Lewis would have been witness to the severe fighting at Brandywine, the Revolution’s bloodiest day. After the decisive British victory at Brandywine, the Minnigerode Battalion along with the rest of the army moved to occupy the Rebel capital of Philadelphia. This victory was relatively short lived, if not shattered, when unexpectedly on the morning of October 4th, 1777, General George Washington’s army surprised and overran British forces in Germantown. Count von Donop’s command then acting as a reserve, was hurried forward as reinforcements and played a part in helping reverse the tide of the battle. The next week or so consisted of general duties, such guard mounts, patrols, and, in some cases, small skirmishes with the enemy. Not even ten months had gone by since Prince enlisted, and already, he was certainly a veteran of hard-fought battles, severe campaigning conditions, and some of the American Revolution’s key moments. All this experience would certainly be needed in the next chapter of his experience.

Forts’ Mercer and Mifflin had proved to be a thorn in the British ability to effectively control the greater Philadelphia region, particularly the Delaware River. Several attempts at reducing Fort Mercer failed, and it was finally determined that it would need to be taken by direct assault. Count von Donop was selected for this task, in part to offer an opportunity to erase the stain of the previous winter’s campaign. Returning to New Jersey via Cooper’s Ferry, Lewis and his fellow drummers led the Hessian Grenadier Brigade and the Mirbach Regiment towards Fort Mercer. The Hessians were launched at the fort on its north side; Minnigerode’s grenadiers managed to scale the ramparts of an abandoned section of the fort. Mercer’s defenders, most notably the 2nd Rhode Island Regiment, had abandoned part of the fort to contract their lines and provide a better defense. The Minnigerode Battalion then surged toward the other portion of the fort, only to be confronted by a tangled mass of felled trees with pointed branches that protected the main wall of the fort. With no tools, the Hessians began to claw their way through the barricade, where they were quickly spotted and fired on by the defending Americans above. The slaughter was great, and the Americans were handed one of the most lopsided victories of the war. Hundreds of Hessian soldiers were shot down in just less than 40 minutes. Amongst the many lifeless bodies surrounding the fort was a young, now 27-year-old drummer named Prince Lewis. His short military service sincerely reminds us that the American Revolution was a much more complex issue than we sometimes remember. It also reminds us that the road to liberty has many different paths and meanings to the individual.

For further background information see:

“Lewis, Prince (ca. 1752 – 1777)“, in: Hessische Truppen in Amerika <https://www.lagis-hessen.de/en/subjects/idrec/sn/hetrina/id/4583> (Stand: 20.1.2015).

“Journal of the Honourable Hessian Grenadier Battalion at one time von Minnigerode later von Loewenstein. From January 20th 1776 to May 17th 1784,” K. 77, fiche 232, Letter K, Lidgerwood Collection, Morristown National Historical Park, Morristown, NJ.

Photo from Kabinettskriege: Ab Eighteenth-Century Digital Humanities Project – http://kabinettskriege.

Written by Colin Zimmerman, Military Historian for the Friends of Washington Crossing Park.